Early this year, staff from the University’s Office of Environmental Health and Safety (EHS), in preparing for the move to the new chemistry building, found a filing cabinet in the Frick Laboratory (currently home of the Chemistry Department) containing material related to Princeton’s involvement with the Manhattan Project. (While the common perception of the Manhattan Project is that it was physicists doing the work, a great part of the effort involved chemists too.) Many of the documents were labeled as classified, though some were stamped with Declassified stamps from the 1950s. EHS Director Garth Walters sought advice from the General Counsel’s office and Val Fitch (emeritus professor who worked in Los Alamos during the war). Fitch did not believe any of the documents were still classified, but until that was definitively determined, the General Counsel’s office suggested that a more secure place be found for the cabinet, and hence a call to the Mudd Library in March.

University Archivist Dan Linke readily agreed to house the file cabinet, and the day after doing so, he received a call from Sue Dupre, also in Environmental Health and Safety and the Radiation Safety Officer for the University. She reported that while the filing cabinet itself is uncontaminated, some of the lab notebooks within the cabinet were radioactive! The notebooks had apparently become contaminated with uranium in the 1940s while they were being used during experiments. However, the amount of radiation emitted by the uranium on the notebooks was at a level that did not penetrate the filing cabinet–and only the bottom two drawers contained material that was “hot.” When Linke asked her how hot, she said that of the four scales on a Geiger counter, they were at the “high end of the lowest scale,” but reassured him that there is no measurable reading from the outside of the cabinet and that one is subject to far more radiation from jet travel or other natural environmental circumstances. Although the uranium appeared to be fixed to the paper of the notebooks and would not readily transfer to the skin of people handling the notebooks, Dupre recommended that the notebooks be handled with latex gloves as a precaution.

After working with the U.S. Department of Energy to determine that the records were indeed no longer classified, Linke was faced with the question of what to do with the radioactive notebooks. In all of the archival literature on appraisal, there is no mention of radioactive documents. Said Linke, “During my 20+ year archival career I have had to worry about wet documents, moldy paper, insect and vermin residue, and other unpleasant things, but this is the first time I have had to deal with radiation.”

Calling around the University for help, Linke found R. Scott Kemp, a Woodrow Wilson School doctoral candidate in the Program on Science & Global Security. A physics major as an undergraduate, he also serves as an occasional consultant to the U.S. Government on nuclear-proliferation matters. Kemp enthusiastically agreed to assist the library in determining the disposition of the materials.

After reviewing the materials, Kemp determined that the material “relates to chemistry research performed at Princeton University’s Chemistry Department in support of the U.S. Manhattan project… This activity was organized under the “Madison Square Area” of the “Manhattan District, Corps of Engineers,” which was tasked with identifying sources of uranium for the first nuclear weapons.” However, the radioactive notebooks “contain primarily measurement data on tested samples; they are not informative with respect to the critical technical achievements of the Manhattan Project, nor the difficulty of sourcing uranium, nor the development of new analytical methodologies. The archive does not contain information of contemporary scientific interest.”

Based on Kemp’s information, Linke decided to retain the paper files, but to discard the notebooks. Working with Sue Dupre, the material will be responsibly discarded with other radioactive materials in accordance with University radioactive waste procedures (A few non-radioactive notebooks have been kept for possible exhibition value.)

A serendipitous request occurred just around the time we received the filing cabinet. An alumnus, Bruce McDuffie, who graduated with a PhD in 1947 called to ask if his doctoral dissertation was available in the library. He explained that he worked on a classified topic and when he graduated the dissertation was restricted. Mudd Library is the University’s repository for all doctoral dissertations but McDuffie’s was not found in our holdings. However, in reviewing the Manhattan Project filing cabinet, several dissertations were discovered, including McDuffie’s entitled “A Critical Study of the Electrolytic-Polarographic Method and Preliminary Investigations with the Mercury Diaphragm Electrolysis Cell” and these will be cataloged and added to Mudd’s dissertation collection.

For more information on these Manhattan Project records, see our online finding aid.

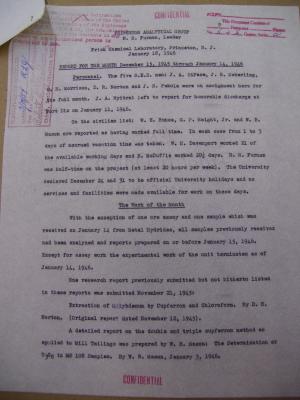

Pictured above: filing cabinet where notebooks were housed.