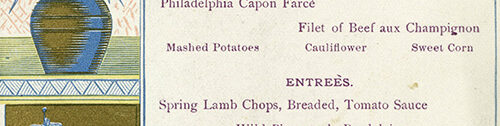

If you spend as much time immersed in the University Archives as I do, at times you will see intriguing patterns emerge. I have seen repeated examples of an unusual theme in the graphic arts associated with the College of New Jersey (as Princeton University was named until 1896) in the late 19th century and early 20th: a variety of seemingly out-of-place Asian imagery. For example, a menu for what is clearly Western-style food, written partly in French, features a drawing of potted bamboo and a person in a kimono. One finds drawings of Asians in the Bric-a-Brac’s section headings, though not in settings where any logic would imagine they would truly appear at this time, such as working as clerks in the Registrar’s office. The appearance of the “Mikado” eating club in the 1896 Bric-a-Brac, however, should clear up any confusion about the origins of these themes.

This post is one of two in our Department of Special Collections today about the same phenomenon in the Western world through the lens of different collections under our care, as people throughout Europe and North America had a sudden fascination with all-things Japanese in the latter half of the 19th century. On the Graphic Arts blog, today Julie Mellby examines the printed illustrations in the Narrative of the Perry Expedition’s establishment of diplomatic relations between America and Japan in the 1850s that sparked this trend. Another post planned in the coming weeks from Emma Sarconi on the Manuscripts News blog will show what our collections have to tell us about “The Mikado,” a Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera set in Japan that was first performed in London in 1885 and quickly spread throughout the English-speaking world—even, it appears, to the extent that a group of students named their eating club after it.

All of this Asian-themed imagery is not truly out of context, but rather represented the zeitgeist of this era in a way that illustrates just how pervasive the phenomenon truly was in the Western world. Students of art history will already know about the influence of Japanese themes on artists like Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet, but the ripple effect was much larger. Casual use of these images in places we’d never be likely to find them in 21st-century graphics shows how Princetonians adopted the fad as their own and made it a part of collegiate life. In doing so, they enfolded depictions of Asians into a broader trend of portraying nonwhite races in dehumanizing ways in their ephemeral artwork, as caricatures and/or as mascots, rather than in ways that respected them as part of the community.

This is especially true within the context of Princeton’s demographics at the time, since it was not merely Japanese-style art that appeared on campus. We believe the first students from Asia arrived in the latter half of the 19th century. The Catalogue of the College of New Jersey lists five students from Japan as having been undergraduates at Princeton in the 1870s: Rioge “Rio” Koe, Yokichi Yamada, Girota Yamaoka, Hikoichi Orita, and Hidemaro Namboo. Koe and Yamada had been students at Princeton Theological Seminary before entering college, and the Nassau Literary Magazine reported on the potential for their entrance as a positive development: “We hope many more of their countrymen will follow their example.”

Orita had come to Princeton via Rutgers, which had a significantly greater Japanese presence than Princeton. Indeed, this small wave of Japanese students reflects a larger historical trend. Over 11,000 Overseas Study Passports were issued to Japanese youth between 1868 and 1902, and more than half of these were for study in the United States. Orita’s senior oration in 1876 reflected on the change in relationship between America and Japan. Accounts of his speech indicate that he delivered it in Japanese, but an English translation was published in the Lit:

Through all the mutations of twenty-five centuries, Japan maintained her seclusion unbroken, until the Americans having knocked restlessly at her gates, obtained admission to that ancient empire, whose shores had been almost forgotten by the world. She is now awakening from her dream of ages, and is entering upon a new life.

The overall positive tone in the sources about Japan and Japanese people from the writings of the Western students and the general openness to the West expressed by the Japanese students I’ve found suggests that the imagery was intended to be positive as well. However, we might view it more critically today, just as we would the other depictions of nonwhite peoples in Princeton’s graphic arts of the same era.

America’s romanticizing of Western relationships with Japan and the Japanese through Western art in the 19th century is comparable to their now much more familiar practice of adopting indigenous and African American themes in imagery, symbols, and logos. Had this been more than simply a passing fad of the 19th century, the kinds of conversations we have had in our own time about college mascots, brands of pancake mix, and logos on packages of butter might also be occurring regarding Japanese themes in Princeton’s ephemeral artwork. Indeed, if eating clubs had been the permanent fixtures they would later become when “Mikado” was established on campus and it had persisted as did the more-familiar Ivy or Cannon, we might have been having that conversation locally over the past few years. Although this was ultimately a short-lived trend in American ephemeral art, we are left with sources in the University Archives that give us opportunities to think through what hidden legacies prior generations of Princetonians may have passed down to us, and what this may mean for us in our own time.

Sources:

Catalogue of the College of New Jersey at Princeton

Hikoichi Orita Diary (AC033)

Princeton University Class Records (AC130)

Triangle Club Records (AC122)

For further reading:

Armstrong, April C. “Eating Clubs and ‘The Street.’”

__________. “Yellowface in Princeton University’s 20th Century Triangle Club.”

Duke, Benjamin. The History of Modern Japanese Education: Constructing the National School System, 1872-1890. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009.

Maruki, Yasutaka. “Nose Sakae’s Study Abroad: Idealization and Devaluation of American Education During Japan’s Early Meiji Era.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 115, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 38-59.