By April C. Armstrong *14

Dear Mr. Mudd,

Have there been any Princeton students who went to prison for serious crimes?

Although there are some Princetonians who have ended up in prison for their infamous deeds, including James Hogue (alias Alexi Santana) and Lyle Menendez, it’s probably more commonly the case that in the past students committed serious crimes but did not end up incarcerated for them. Here are five of the most significant 19th-century cases we’ve uncovered.

Stabbing at Morning Prayers, 1805

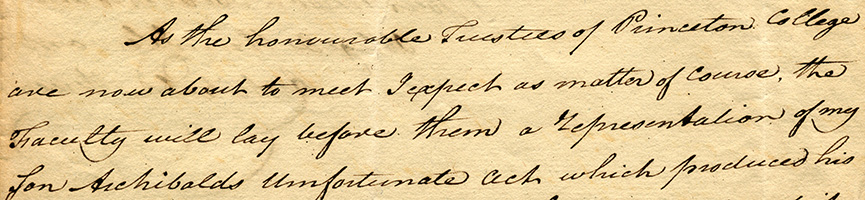

On August 15, 1805, Archibald Mercer lay down on a bench in Nassau Hall prior to morning prayers. He wanted more room for lounging, so he asked a fellow student, John Glascock, to move so he could have more of the bench. Glascock refused. Mercer responded that he would “make him,” pulled a pen knife out of his pocket, and thrust it at Glascock. The first time, he cut a hole in his gown; the second, he stabbed Glascock in the thigh. When he attempted a third thrust, Glascock opened his gown to show Mercer that he’d already been stabbed, at which point Mercer stopped his attack.

There were several witnesses to the stabbing, but Mercer tried to cover his tracks by immediately telling the College president, Samuel S. Smith, that he’d accidentally injured Glascock with a pen knife in his dorm room earlier. Later, Mercer told a friend he’d “told Dr. Smith a falsehood.” When the faculty questioned Mercer about this, he said that Glascock had tried to sit on his head, and he “did not intend to wound him so badly as he had done in the heat of passion.”

For this crime, committed before many witnesses and to which Mercer had confessed to multiple people, Mercer’s only punishment was a suspension from Princeton. Mercer later returned and graduated with the Class of 1808.

Attempted Murder of the College President, 1844

Although College rules prohibited students from carrying weapons, Edward Jones, Class of 1847, usually carried a pistol. After dinner with some classmates in town on January 27, 1844, Jones passed by the study of the College president, James Carnahan, whom students often referred to as the “Boss.” According to a witness (Edward Shippen, one of the students walking back to Nassau Hall with Jones), Jones then said, “The Boss is sitting in there! I’ll give him a shot.” Shippen reported being surprised when Jones pulled out his pistol and fired it through the study window. Jones narrowly missed hitting Carnahan, then took off running. The other students, in stunned silence, walked slowly back to their rooms.

“By Jove! I believe I shot the Boss!”

Edward Jones, Class of 1847

Aside from the witnesses who were present, there was other evidence that Jones had done this. Jones also confessed his crime to his roommate upon his return to their room—“By Jove! I believe I shot the Boss!”—and another student overheard him and recognized his voice. Immediately, that student informed a professor, John Maclean. The next day, the faculty met to discuss the matter. Jones was expelled, but faced no other consequences.

Rioting and Assaulting Police Officers, 1855

What would later be dubbed Princeton’s annual “horn spree” (and morphed into “Poler’s Recess”) annoyed local residents for years, and often amounted to essentially one big riot. It generally consisted of students gathering at a specified time one evening to blow horns, beat drums, and otherwise make as much noise as possible. Consequences often included broken windows and aggravated, sleep-deprived locals.

On September 11, 1855, the “horn spree” became particularly dangerous. Students reported to the Newark Daily Advertiser that they were merely “serenading” a professor outside his home (Stephen Alexander) when suddenly:

they were assailed by Mayor Martin, constable Hullfish [sic], and a large posse of special policemen, who had been sworn in for the occasion, armed with pistols, knives and clubs, and without giving any notice of their intention, immediately felled several of the students to the ground, and attempted to arrest several others.

Locals disputed this claim, saying the only “special policeman” who had been sworn in was Assistant Marshall H. B. Duryea, and the only person with them was the mayor. However, after being violently struck with canes, they called for help from townspeople to handle the mob of about 150 students.

Others reported that the students had shouted the well-known battle cry, “Nassau, Nassau!” which was used to get all the undergraduates to band together and fight against townspeople at various times. Students resisted arrest, and in the resultant brawl, Hulfish was stabbed three times. Hulfish was left in critical condition. Duryea was also injured. Students vowed that if any one of them was arrested, they would all fight against it together, no matter how many they fought against. Multiple students were said to have been injured in the riot.

As reported in the New York Daily Times, the perpetrator of the stabbing was captured, but after he had been taken to the mayor’s office, students smashed the building’s windows. A report in the New York Herald credited professor George Musgrave Giger with persuading the mob to stop with just breaking the windows, rather than carrying forth with destroying the entire municipal building. Somehow, the student—Samuel White Oliver, Class of 1856—made bail of $1,000 and awaited trial.

Ultimately, four students most directly involved in the events, including Oliver, were criminally charged. At Oliver’s trial, one student reportedly said he had resisted arrest because he had seen a Black man among the group trying to arrest them and thus he presumed they had no authority to do so. The jury found Oliver guilty of assault and battery on officer Hulfish, at which point the other three changed their pleas from not guilty to guilty to avoid trial. All were fined $20 each and court costs. None were incarcerated. The judge who sentenced them said that, despite what the defense had argued, the case had nothing to do with local prejudice against Southerners (the students in question were from the South). The Trenton State Gazette explained the light sentencing:

The only act which it was proved he [Oliver] committed was simply knocking a man down who laid hands on him, and who was merely an assistant of an officer, the student being unaware he was acting in an official capacity. Such an act was not one of “moral turpitude or dishonor.” … Their offence [sic], under the circumstances, was considered only a slight infraction of law.

Rioting and Manslaughter, 1867

When a visiting military company and Princeton students got into an argument in 1867, it quickly turned violent. The problems began when the Princeton Guards hosted counterparts from Newark. The military visitors claimed students had insulted them, and this is why they attacked them. The students called for help from their peers in accordance with mid-19th century custom. The resultant brawl, in which the two mobs threw rocks at one another, turned deadly for Daniel Sullivan, one of the College servants. John Maclean reported to the Board of Trustees that Sullivan, who was not involved in the conflict but had been caught in it when he was trying to walk home, “received a severe blow upon his forehead just over his left eye.” A few weeks later, Sullivan died from his injuries. Maclean requested the Trustees authorize payment of $200 to Sullivan’s widow to pay off their mortgage and help care for Sullivan’s young children, but he did not mention any disciplinary action or civil consequences for anyone involved. The College itself was penalized, however: the town hired more police to ensure the students would not engage in any further “acts of violence and indiscretion” and fined the institution $37 to offset the cost of the additional staffing.

Assault, Vandalism, and Robbery at a Chinese Laundry, 1893

In 1893, two Princeton students made national headlines for assaulting Sing Lee (also called Theng See in some sources), a Chinese immigrant who operated a laundry on Nassau Street, and his assistant, Lee Why (called See Why in some sources); ransacking the business; breaking the windows; and stealing $85 from Lee. In addition to material losses, Lee and Why suffered burns from hot irons and boiling water.

The students, Edward Munn and Thomas Slidell, both of the Class of 1895, were apparently intoxicated after attending a farewell dinner for a friend on October 12, 1893. After the meal, attendees reportedly loudly paraded through local streets, saw their friend off at the train station, and dispersed. It was about 10:00 p.m. and Lee was at work in the laundry when Munn and Slidell entered and drunkenly demanded their washing. Lee asked to see their tickets, but they didn’t have any. Lee told them he could not give them anything without tickets. Not willing to accept this response, Munn and Slidell began ransacking the establishment, throwing bags of clothes around and dumping the freshly laundered things on the floor. Lee attempted to make them leave, at which point, they attacked him and his assistant. They used the hot irons in the assault and threw boiling water over the two Chinese men. One held Lee down while the other began breaking the windows, the lamps, and everything else that was made of glass. He threw the account books and other paper records about, then went into the back, where there was a kitchen, and ransacked that room as well. It is there that Lee said the student found the money and took it.

“The Chinese are not any too popular with them.”

New York Tribune, October 14, 1893

A report in the New York Tribune said that townspeople heard a disturbance and saw the two leaving the laundry after the assault, vandalism, and theft, but responded by going in to continue to damage the shop and rough up the injured immigrants, because “the Chinese are not any too popular” with Princeton residents. This may explain why the students faced relatively mild penalties for their crimes.

Munn and Sliddel were arrested a few days later. However, they ultimately served no jail or prison time. Slidell asked his mother for help with bail, but she refused; local residents instead came to the aid of both students and bailed them out. Munn offered Lee his money back, but he declined. A Mercer County judge imposed a fine of $50 each on the perpetrators. Press was divided about whether the students should have been civilly punished at all, with the Philadelphia Inquirer urging, “It is time to suppress the college ruffian,” but the Cleveland Gazette complaining that any punishment at all in the county courts was inappropriate.

Civilization is rapidly growing effete and tottering to its fall. The next thing we know college hazing will be dragged into the courts and treated like any other ruffianism.

Sources:

Board of Trustees Records (AC120)

Historical Photograph Collection, Individuals Series (AC067)

Office of the Dean of the Faculty Records (AC118)

Undergraduate Alumni Records (AC104)