by Annabel Green ’26

This is the second in a two-part series about racist propagandist Carleton Putnam, Class of 1924. The first part in this series considered his involvement with Princeton University and beyond during the 1960s. The second post in this series will consider his involvement during the 1970s.

Alumni Perspectives : An Antiquated Princeton

Integral to Carleton Putnam’s argument on race was the notion that the demographics of students at Princeton should remain genetically analogous to what was represented in the early days of Princeton; that is, Princeton should predominantly be composed of white men, preferably with familial connections to the school.

“Every possible step is taken with increasing success to deracinate our founding stocks. […] if these figures stand up, the university no longer belongs to the stock of its founders. Genetically speaking, you have already lost Princeton.”

–Carleton Putnam to Princeton University President William G. Bowen, 1975

Preference for preserving the historical demographics of incoming students was a sentiment articulated among many alumni. In an article written in Prospect titled “It Is Time … For Some Answers,” alum Thomas Harding Jones ’72 expressed negative views on admissions policies and demanded the consideration of alumni opinions when making admissions decisions. Jones was the co-founder and executive director of Concerned Alumni of Princeton (CAP 1972-1986) and editor of Prospect, a conservative monthly publication financed by a group of alumni and published independently by CAP. Putnam and Prospect were not in full agreement, however; the passing of time alongside growing racial diversity seems to be reflected in CAP’s less directly segregationist approach. Still, CAP’s primary motivation was to limit the number of women attending the university. The group also opposed affirmative action, which was designed to increase enrollment of minorities and women. Collectively, they hoped to vocalize alumni dissent. They believed that the university’s actions were moving the institution toward decline. Jones wrote:

“Princeton is an old, private university. The men who founded and nurtured Princeton sent their sons and their sons’ sons to the college […] Princeton exists today because of the men who spent four years with her. Princeton is very much, part of those men. And they are a part of Princeton. They, as alumni, have a legitimate role as custodians of Princeton’s traditions and an obligation as trustees of Princeton’s future.”

Crossroads

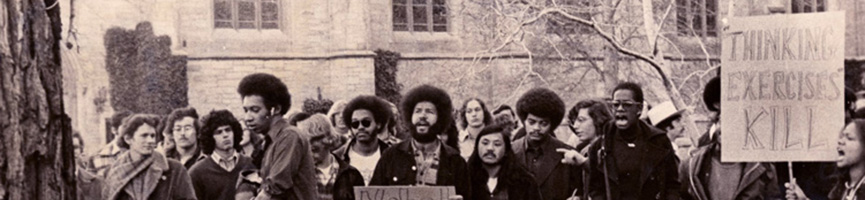

Princeton’s issues with Putnam’s views seemed to come to a head. On one hand, there was a concern for freedom of speech and the expression of opinions, however contentious these opinions may have been. On the other hand, there was concern for the well-being of those whom Putnam’s beliefs targeted. The American Whig-Cliosophic Society invited Stanford professor William Shockley to speak on campus at McCosh Hall. The 1973 Shockley Debate proved to be a very public example of this tradeoff. Shockley voiced similar sentiments as Putnam: inherent racial inferiority and the necessity of segregation. Putnam had explicitly supported Shockley during this time.

A lively discussion followed, and Whig-Clio’s Governing Council decided unanimously that free speech concerns outweighed the need to show respect to any single group, according to a member of the Council, Josh Libresco ’76. Six months after Putnam’s visit to Whig-Hall, Putnam himself expressed disfavor for University president William Bowen’s contempt for Shockley. One could presume that a similar ruling must have been applied for Putnam’s visit to Whig Hall in 1964, especially considering that the community at large would have been more accepting of Putnam’s proposals in his time than of Shockley’s in later years.

Correspondence between the administration and Putnam, as well as between the administration and other alumni who had concerns about Putnam, can be found in the Office of the President Records: William Bowen Series. “Fortunately for all of us there are definite differences among people,” Dean of Student Affairs Adele Simmons wrote in a letter to Putnam on January 3, 1975. “It is the differing talents of individuals that provide [the richness] of many parts of our society.” Politician and alum J. Paul Barringer (Class of 1924) copied Bowen in a November 2, 1973 letter to Putnam in which he wrote

“…you clearly express your opinions which I respect even though my own observations, interpretations and conclusions with regard to the current social scene in America do not coincide with yours.”

Conclusion

Putnam’s influence persisted in the South during the Civil Rights movement and aligned with concerns surrounding admissions expressed by other alumni. However, at large, his argument was deemed neither good nor necessary, despite Putnam’s emphatic attempts at imposing his beliefs.

Sources:

Concerned Alumni of Princeton Records (AC305)

Office of the President Records: William Bowen Subgroup (AC187)

Princeton University Publications Collection (AC364)

Putnam, Carleton. High Court’s “Arrogance” Is Viewed by a Northerner: A Letter to the President. Greenwood, Mississippi: Educational Fund of the Citizens’ Councils, 1958.

Putnam, Carleton. High Journey: A Decade in the Pilgrimage of an Air Line Pioneer. New York: Scribner’s, 1945.

Putnam, Carleton. Race and Reality: A Search for Solutions. Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1967.

Putnam, Carleton. Race and Reason: A Yankee View. Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1961.

Putnam, Carleton. Theodore Roosevelt: A Biography. New York: Scribner’s, 1958.

Shockley, William. Shockley on Eugenics and Race: The Application of Science to the Solution of Human Problems. Washington: Scott-Townsend, 1992.