This is the first installment of a two-part series on the Church at Princeton. The second will appear next week.

By Christina Cho ’24

Introduction: Dropping Out of Princeton

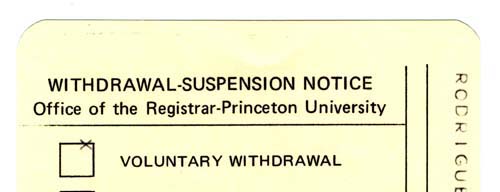

In the spring of 1982, Najib Nicholas Khuri—then a senior in the Slavic Studies department—decided to skip his final exams and consequently failed to graduate from Princeton. Khuri wasn’t alone. Eight other students followed suit, either failing to show up to their final exams or filing formal withdrawals. Together, these students constituted the “core group” of The Church at Princeton (TCAP), a religious movement that Khuri founded during his time as a Princeton student.

After dropping out, these TCAP members spent their summer camping out in the Spelman Hall dormitory awaiting a nuclear holocaust that was purportedly going to take place in New York City on July 24, 1982. (The students had reached an agreement with the university to rent rooms in Spelman before dropping out.) July 24 came and went with little change to the city. However, Khuri apparently claimed that “the destruction had taken place spiritually, but not physically.”

The following fall, Khuri predicted yet another apocalyptic event. This time, he published his “Prophecy to Princeton” in The Daily Princetonian:

Woe! Woe! O Great City! Your judgment is nigh, and the cry shall indeed go forth, ‘Fallen! Fallen! Is Babylon the Great!’ for she is but a habitat of demons and every unclean thing. So shall be the fall of the idols ye worship, O Princeton! So shall be the fall of the city (New York) ye adore, even the city of lights — false lights and lies; the city of humanism — reaching to the heavens with her towers, her multitude of towers, her towers of Babel. (cf. Revelation 18)

Though definitely controversial, this prophecy was not necessarily out of place within its zeitgeist. There was a trend of “apocalyptic speculation“ among televangelists in the 1980s, and it seems that Khuri took inspiration from it. According to the Trenton Evening Times, TCAP members shared “much of their theology“ with Pat Robertson, a popular televangelist who predicted Armageddon through broadcast and published media. We can partially understand Khuri’s prophecy, then, as a reaction to figures like Robertson and the overall “rise“ of televangelism in the 1980s.

So, who were the people who believed in this prophecy? This week and next, I’ll discuss Khuri and other members of TCAP, outlining their lives at Princeton and what happened after they left.

Who was Najib Nicholas Khuri ’82?

Various articles from The Daily Princetonian portray Khuri as a kind of outsider, calling him “shadowy“ and an “underworld character.” One of the earliest articles I found, which was published a few months after Khuri’s departure, describes him:

He was in many ways just as alienated and lost as many of the followers he later gathered. Friends from that time remember him as “painfully shy.”

However, other sources suggest that Khuri was also in some ways a kind of insider. According to the Brownsville Herald, a Texas newspaper, Khuri grew up in an affluent area of the Bronx as the son of a physics professor. The Trenton Evening Times wrote that Khuri also attended two well-known private schools, Collegiate School and Phillips Academy Andover, before entering Princeton. Compared to other TCAP members—whom I will discuss next week—Khuri was far better equipped to navigate the Princeton environment.

However, Khuri suffered from drug abuse as an adolescent and continued using drugs at Princeton. Sophomore year was especially rough for Khuri, who apparently spent much of his time as “an acidhead” (i.e., using LSD). After the school year ended, Khuri decided to take a year-long break in Oxford, England. Why he decided on Oxford is unclear, but he underwent a significant transformation while living there. Khuri, in his own words, “was reborn” (cf. John 3:3).

An article in Prospect, a magazine by the right-wing group Concerned Alumni of Princeton, writes that Khuri met “a couple of members of a charismatic ministry on Oxford’s campus” and afterwards underwent “two exorcisms.” Prospect uses the term “exorcism” to indicate Khuri’s ritual-based conversion, which may be more commonly known as “deliverance” among Charismatic Christians. As anthropologist Thomas Csordas writes in The Sacred Self: A Cultural Phenomenology of Charismatic Healing, deliverance from evil spirits is a major genre of faith healing in Charismatic Christianity. Interestingly, Csordas also notes that the “organized” practice of deliverance (i.e., deliverance held by formal ministries) “peaked” in the mid to late 1970s, which perfectly coincides with Khuri’s stay in England.

After his year in Oxford, Khuri returned to his studies at Princeton and at some point founded TCAP. Although the exact nature of TCAP’s development is unclear, we know that around 12 students joined within a year. According to several articles, Khuri baptized these members in the Fountain of Freedom beside the School of Public and International Affairs. One article claims that Khuri also baptized people in the Dillon Gym swimming pool and Lake Carnegie, which is about two miles away from Princeton’s central campus. Khuri additionally held prayer meetings and gave sermons in Terrace Club, claiming that he spoke “the word of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Although Khuri conducted various religious activities on Princeton’s campus and publicly tried to spread his beliefs, Khuri claimed that he never encouraged students to drop out of college. He said that those who dropped out were personally “led by God“ to do so. It seems that the administration accepted Khuri’s logic. In an interview with The Princeton Packet, Robert Durkee, who was then the vice president for public affairs, said:

One of the things I know Najib has said is that other students have taken their actions without his encouragement […] The other students have apparently received their own messages.

Durkee’s statement, which basically reiterates Khuri’s claims, suggests that the administration officially adopted Khuri’s position as their own. The following quote from Hector Delgado, who was then the assistant dean of student affairs, further confirms my suspicion that the administration—at least officially—chose not to respond to Khuri’s religious activities:

What makes this situation particularly difficult for the administration is that it concerns religion. Making a distinction between conventional, acceptable religious behavior and dangerous, unacceptable behavior is difficult and not really our right.

Although Delgado claimed that the administration could not distinguish between “acceptable” and “dangerous” religious activity, other evidence indicates that administrators were in fact concerned about Khuri and his potential to influence other students. Khuri had dropped out of Princeton, but he and other TCAP members were still around campus in the fall of 1982. Before the semester began, assistant dean of the college Richard G. Williams “spoke to the RA’s about Khuri’s group at a three-day training session” but “did not suggest that the RA’s take any concrete measures.” The administration’s ambivalent stance meant that Khuri could roam around campus without facing any consequences. Indeed, it seems that Khuri spent the next school year hanging out in various campus locations and eating his meals in Terrace Club. Aware of his own immunity, Khuri said the following to The Daily Princetonian in December 1982: “They have nothing on me.”

Other TCAP members were less fortunate than Khuri. Of the eight other members who dropped out, four—Kimberly Ann York ’84, Stephen Blair ’84, Terry Rodriguez ’84, and Denard Edwards ’84—were eventually sentenced to a few months in jail for trespassing at a local church. Next week, I’ll discuss the information I found on these individuals and what happened leading up to their sentence, which they received in May 1983.

Sources:

Harley, Richard M. “Toying with the Apocalypse.” Christian Science Monitor 2 August 1982: 22.

Historical Subject Files (AC109)

Office of the Dean of Religious Life and of the Chapel Records (AC144)

Office of the Dean of the College Records (AC149)

Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Students Records (AC136)

Office of the President Records: William G. Bowen Subgroup (AC187)

Princeton University Publications Collection (AC364)

Undergraduate Academic Files (AC198)

Undergraduate Alumni Records (AC199)

For further reading:

Csordas, Thomas J. The Sacred Self: A Cultural Phenomenology of Charismatic Healing. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Hadden, Jeffrey K. “The Rise and Fall of American Televangelism.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 527 (May 1993): 113-130.

Toulouse, Mark G. “Pat Robertson: Apocalyptic Theology and American Foreign Policy.” Journal of Church and State 31, no. 1 (Winter 1989): 73-99.

6 responses to “The Church at Princeton, Part I: Najib Nicholas Khuri ’82”

This article is extremely misleading. I was part of the original fellowship in 1982. Najib did not tell us to drop out of school or trespass or become persona non grata like this article implies. Najib also warned against the writing and dissemination of a provocative letter, the content of which he profoundly disagreed with, that got a few of the students in trouble.

Different people did different things, all of their own accord. For example, I decided to drop out but did not provoke persona non grata status and did not trespass. Neither did Najib. Actually, of the students who withdrew, he was the last not the first and never encouraged those who were before him to do so.

My best friend in the fellowship, who became one of the most devoted Christians among us, did none of the above, and she went on to graduate and become an excellent corporate lawyer.

Najib always told us to be “led by the Holy Spirit” (from the book of Romans and Galatians) in the “integrity of our heart” and, rightly or wrongly, we really ran with that. In hindsight, we were all young college students and definitely immature, but the issues ultimately reflected our youthful excesses more than any one person.

Looking back, Najib overall helped me to be less focused on petty stuff, and to think about the real purpose of life, which I still appreciate, even many decades later.

Finally, for those who wish to be more discerning, there is something amiss about putting forward a person’s life for public spectacle over 4 decades after the events took place. It is particularly harmful when this outdated calumny (almost half a century old) comes suddenly online during a time at which Najib has a daughter fighting for her life with metastatic cancer (I recently visited her in the hospital) and is suffering himself with a brain tumor and Parkinson’s disease. He and his family need prayer and support, not condemnation for the controversies of the past.

I have to question the motives of those behind these articles, especially when they are so cleverly written to make implications that are verifiably not factual or to twist things repeatedly in order to undermine someone I know to be a good human being. Najib was colorful and very outspoken, but he wasn’t, and isn’t, the sinister figure insinuated in these articles.

Najib Khuri now goes by Nicholas Khuri. He brought me into a small religious group that revolved around his private religion and his charismatic personality back in 2006-2007. He lay waste to my life during that year and a half. I am still recovering from that involvement.

Could you send me, Kimberly York, an email. Love to chat. Obvious some doors aren’t closed. Zengardenoffice@gmail.com

[…] This is the second installment of a two-part series on the Church at Princeton. The first appeared last week. […]

I knew Najib, a nice but terribly misguided fellow, and wonder whatever became of him and his followers.

This is Kimberly York, I was one of the core group of the Church at Princeton in your article. To contact me email me at ZenGardenOffice@gmail.com

If you would like to know what happened to the group.