By Travis York ’23

with April C. Armstrong *14

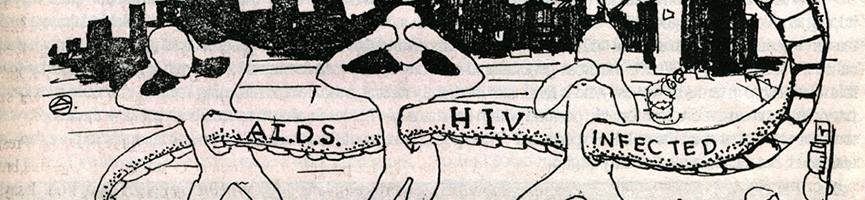

In this, the second part of the story on AIDS awareness on Princeton University’s campus, we will cover the representation of AIDS and queerness within selected student newspapers and alumni publications.

While all of the United States began to discuss AIDS in the 1990s, especially in relation to sexual orientation, some student newspapers began to discuss queer identities more broadly. These newspapers provide a unique look into how conversations surrounding sexual orientation began and continued on Princeton University’s campus and represent at least one sector of campus in which these discussions on sexual orientation and AIDS were occurring. Though we see less coverage in publications like the Daily Princetonian or the Nassau Literary Review, some newer campus periodicals, especially the Progressive Review and Nassau Weekly, began to include more coverage of queerness as AIDS also rose in public consciousness.

“AIDS-AIDS-AIDS-AIDS-AIDS-AIDS. Please do not stop reading this article.”

Sara Goltz ’96, progressive Review, November 1993

The AIDS epidemic’s role in growing conversations around sexual orientation was crucial. As early as 1987–the same year that ACT-UP (AIDS Coaltion to Unleash Power) formed at New York’s Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center to address national neglect of the crisis in gay men’s health–students were claiming that the university “has not shown enough support for AIDS discussion and help,” in response to the funding the Bisexual and Lesbian Support System (BLSS) had received from the university, according to November 4, 1987 article in the Prince. As Jennifer Kates *95, the Staff Assistant for the LGBA at the time, observed in the December 1992 issue of the Progressive Review, “Without the dramatic response of AIDS activism to the AIDS crisis, we would not have such a powerful and organized queer community today.”

As a growing epidemic within the United States, AIDS was frequently connected to queerness, yet was also covered as its own topic, with four causes for the epidemic identified as homosexual and bisexual men, Haitian immigrants, intravenous drug users, and hemophiliacs. While Haitian immigrants were taken off of the risk factor list in April 1985, the public connection between these groups and AIDS presented an obstacle for activists to overcome. The response to AIDS in the United States brought together many queer activists, planting the seeds for the modern queer liberation movement.

At Princeton, just as in America at large, there were direct links made between AIDS and minority sexualities. One dramatic example from the broader culture occurred with the January 1988 publication of an article in Cosmopolitan offering “Reassuring News about AIDS” for heterosexual readers. The reassurance was as follows: “There is almost no danger of contracting AIDS through ordinary sexual intercourse.” If there was no serious risk–a claim that physicians and public health services both then and now would dispute–then it wasn’t something heterosexuals should worry about or even think about. Indeed, many didn’t. Instead, this increased the general social stigma for minority sexualities.

Students at Princeton also felt this stigma. In May 1986, the editor-in-chief of the Progressive Review, Joel Anderson ’87, wrote about “The Invisible Minority” (gay and lesbian students on campus). Concerning the hindrances to coming out of the closet for many gay and lesbian students, Anderson noted that

the anatomy of homophobia on campus is complicated. In the first instance, it seems to be a matter of heterosexism, the view that heterosexuality is the only legitimate form of sexual orientation, and that homosexuality is wrong or perverse. This is a bias in our culture, which has gained monstrous proportions with the AIDS scare, and which is constantly reinforced by stereotypes and misconceptions about what most gay men and lesbians are like.

![A cartoon man wearing a t-shirt that reads, "This [triangle] is pink" who is saying, "We had wanted to have someone homophobic in this space but everybody was afraid to appear in conjunction with this article."](https://i0.wp.com/universityarchives.princeton.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/2023/08/Homophobia_cartoon_Disorientation_Manual_1990_AC364_Box_14.jpg?resize=650%2C749&ssl=1)

Still, as the AIDS crisis grew in the United States and activism around the virus jump-started in New York as noted above, AIDS rhetoric also penetrated Princeton University’s “orange bubble.” Student newspapers increasingly began to report on sexual orientation and include articles in their publications from those involved in queer and AIDS activism. However, it is important to note that there was a difference between AIDS activism and queer activism as a whole. Kates put it this way in the December 1992 edition of the Progressive Review: “AIDS Activism was an important precursor to Queer activism, as something related to but distinct from the lesbian, gay, and bi liberation movement.” It may be better to understand it as a transition in an existing movement. While queer activism had long existed, even on Princeton’s campus, AIDS activism pivoted and heightened campus controversy and talk around sexual orientation and queerness.

AIDS discussions reached alumni as well. The Princeton Alumni Weekly (PAW) ran an article on opera singer Will Parker ‘65 and his battle with AIDS written by Dan White ‘65 on May 6, 1992. The article received a number of letters to the editor in response, some of which were printed in the July 8, 1992 issue. Positively, Arthur Rosenblatt ‘60 wrote that in sharing Will Parker’s story, the article served as “a reminder that AIDS makes no distinction in its selection of victims…”

However, not everyone was pleased with the PAW covering AIDS. John Nevius ‘42 commented that Parker “flaunts having contracted it through unhealthy practices of a so-called alternative lifestyle.” This was a common line among Americans in general, in which many people claimed to have a problem not with the existence of queer people and people with AIDS but with their “flaunting” of gay identity, a problem gay activists told the Washington Post about in 1993 (“Gay Activists Summon Their Hopes, Resolve,” April 18, 1993). In his 1992 letter, Nevius went on to state, “It seems to me wrong for PAW to lionize the very lifestyle that initiated the AIDS epidemic in this country.” Nevius’ comments struck a common chord with Americans in the 1990s who still viewed LGB people as the catalysts of the AIDS epidemic. The discussion of AIDS within undergraduate and alumni circles represents a continued denial of the impact AIDS has on all people, regardless of sexual orientation.

As attention to both AIDS and queerness spiked in public discourse, Sarah Goltz ’96 created the Princeton AIDS quilt – an 8’ x 11’ quilt resembling the national AIDS Memorial Quilt for current and past Princeton students lost to AIDS. She claimed in the November 1993 issue of the Progressive Review that many students ignored the AIDS epidemic, writing that “the big problem is that for some reason people still think that this pandemic is not affecting our community.” The quilt was one way of addressing that.

At the time, AIDS was seen as a similar yet distinct issue from queerness. While AIDS conversation remained somewhat taboo, it grew within newspaper circulation while it bolstered more conversations on campus around sexual orientation. Yet as understanding of AIDS as an illness anyone could get began to grow in the 1990s, its connection to queer activism began to fade somewhat. The Red Ribbon Project formed to raise awareness of AIDS, kicking off its first major campaign by persuading attendees at the 1991 Tony Awards to wear red ribbons in solidarity with artists and performers suffering from AIDS. Quickly, other industries followed suit, with these red ribbons spreading through the Oscars, Emmys, Grammys, sporting events, talk shows, political conventions, and more. As AIDS itself was understood to be mainstream, so too was AIDS activism, while queer activism remained on the fringes of society.

The distinctness of AIDS activism and LGB activism can be seen mapped along the curves of Princeton University’s campus discussions. Student organizations like GALAP would appear within the Princeton scene to advocate for an inclusive environment for LGB students. Still, even within these groups, evidence of the discussion of AIDS is limited somewhat.

Some expressed frustration with this situation. In November 1993, the campus was greeted with these opening words from Goltz in the Progressive Review: “AIDS-AIDS-AIDS-AIDS-AIDS-AIDS. Please do not stop reading this article.” Goltz went on to emphasize that the national focus on heterosexuals who contracted AIDS had put others at greater risk because of the lack of concern for their particular needs and urged Princetonians to make a point of caring about the queer alumni and students who would be infected and die if the trend of neglect continued, both nationally and locally.

While conversations directly surrounding AIDS may not have been pervasive on Princeton’s campus, the impact of AIDS cannot be overstated. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, campus conversations surrounding queerness and sexual orientation erupted in ways they had never done before. As a reflection of the country itself, Princeton was not left out of a broader national conversation. Indeed, it mirrored it. From Arthur Eisenbach’s 1972 classified ad to the multitude of voices in the 1990s, a drastic change in the openness of discussing these issues on Princeton University’s campus occurred. AIDS had brought sexual orientation to the forefront at Princeton.

Sources:

Lesbian Gay Bisexual Alliance Records (AC037)

Princeton University Publications Collection (AC364)

Office of Communications Records (AC168)

For Further Reading:

Andriote, John-Manuel. Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Armstrong, April C. “‘Wear ‘Em’: Princeton University’s First Gay Jeans Day.”

Bruce, Katherine E. and Lori J. Walker. “College Students’ Attitudes About AIDS: 1986 to 2000.” AIDS Education and Prevention, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2001, 428-437.

Cohen, Cathy J. The Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Lee, Motoko Y., Alphonso R. Campbell, and Charles L. Mulford. “Victim-Blaming Tendency Toward People With AIDS Among College Students.” The Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 139, No. 3, 1999, 300-308.

Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2021.

Walters, Suzanna Danuta. All the Rage: The Story of Gay Visibility in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.